Expressions of power-over - The Censor

Have you ever been in a personal or work situation where the conversation left you feeling bored, numb or dull? Or perhaps there was a time when you felt blamed, shamed or isolated, even made to feel like the scapegoat. These feelings often arise in situations and exchanges when we are unable to say what we really think and feel: when we are being censored by others, or censoring ourselves. In contrast, bring to mind a conversation that felt meaningful and open. How did you feel after? Energised, inspired, moved? When we can use our voice, and connect with others to share meaning, it can spark new ideas and fresh thinking, and help build trusted relationships.

The Censor is one of Starhawk’s ‘five ‘entities of control’ expressed in a power-over paradigm

Return for a moment, to those dull feelings, perhaps in a meeting, or social occasion. Reflect on what isn’t being said, on what lies in the undercurrents of the group dynamic. There are many reasons why we might feel we cannot speak freely in a situation: dominance of other voices; fear of judgement, conflict or repercussions; feeling that what we have to say will be perceived as unimportant, or inarticulate; concern for the feelings of others; lack of accommodation for our needs or styles of communicating; or physical embarrassment and nervousness. Of course, not all these reasons, or others not mentioned, are related to a feeling of censorship. In other instances the differences in use of language, personal experience, cultural context etc may feel too vast a divide to bridge. In these instances we have to ask ourselves what is the desired or necessary connection and understanding, and what value will that bring to those involved.

We can also ask the question, what is the intended outcome of censorship? It is important to become aware of the times when we are censoring ourselves or being directly or indirectly censored by others, as censorship is one expression of a power-over paradigm. Power dynamics are always at play, and frequently govern how we communicate and relate to each other, and in turn what is perceived to be of importance and priority by individuals or groups. We see daily the consequences of power and decision making that serves only a few, already privileged people. In situations that still uphold a hierarchical structure of leadership, it may be difficult to affect positive change that is equitable and fair. Hope lies with leaders that want to build more inclusive and collaborative teams, organisations and societies; and in raising awareness of tools and approaches that can support this shift in how we communicate and relate to each other.

Deep Democracy - lowering the waterline

Deep Democracy is one such communication approach that can support this shift in how we communicate. Deep Democracy is a facilitation, decision making, conflict resolution and inclusive leadership methodology, developed by psychologists Myrna & Greg Lewis and inspired by Arnold Mindell's Process Orientated Psychology.

At the heart of Deep Democracy is the metaphor of the iceberg. The process works to lower the water line: to surface more of what is in the unconscious of the group, and make it conscious and known to everyone. This lowering of the water line is the aim of any facilitated communication method.

Common threads in facilitated communication methods are

Be inclusive of all voices

Acknowledge and welcome thoughts and feelings

Redistribute power

Harness the collective intelligence of the group

We can see these threads in the 4 steps of the Deep Democracy approach:

Gain all the views

Make it safe to say ‘no’ or the alternative view

Spread the no

Vote, and incorporate the wisdom of the minority by asking them what they need to come along with the vote.

What we might call the USP of Deep Democracy is a safe yet courageous process for first uncovering, and then exploring any polarities that surface, if the minority refuses to come along with the vote. Moving to a ‘debate’ invites participants to express statements from the perspective of both polarities, without directing these at any particular person in the group. Expressing statements from both sides allows the group to explore both perspectives, and in the reflection after, to surface any insights that may inform or transform decision making.

The uncovering of group insights in the Deep Democracy process is also a primary feature of the Bohm Dialogue process. David Bohm described insights as having, “some universal sort of significance.” and stated that in the primary act of insight, “we see…a whole range of differences, similarities, connections, disconnections, totalities of universal and particular ratio or proportion..”

Communication challenges - behaviours to look out for

Uncovering insights may be at the more elusive end of these communication practices and processes. As a starting place, Deep Democracy also offers powerful diagnostic tools to assess the current communication challenges within groups.

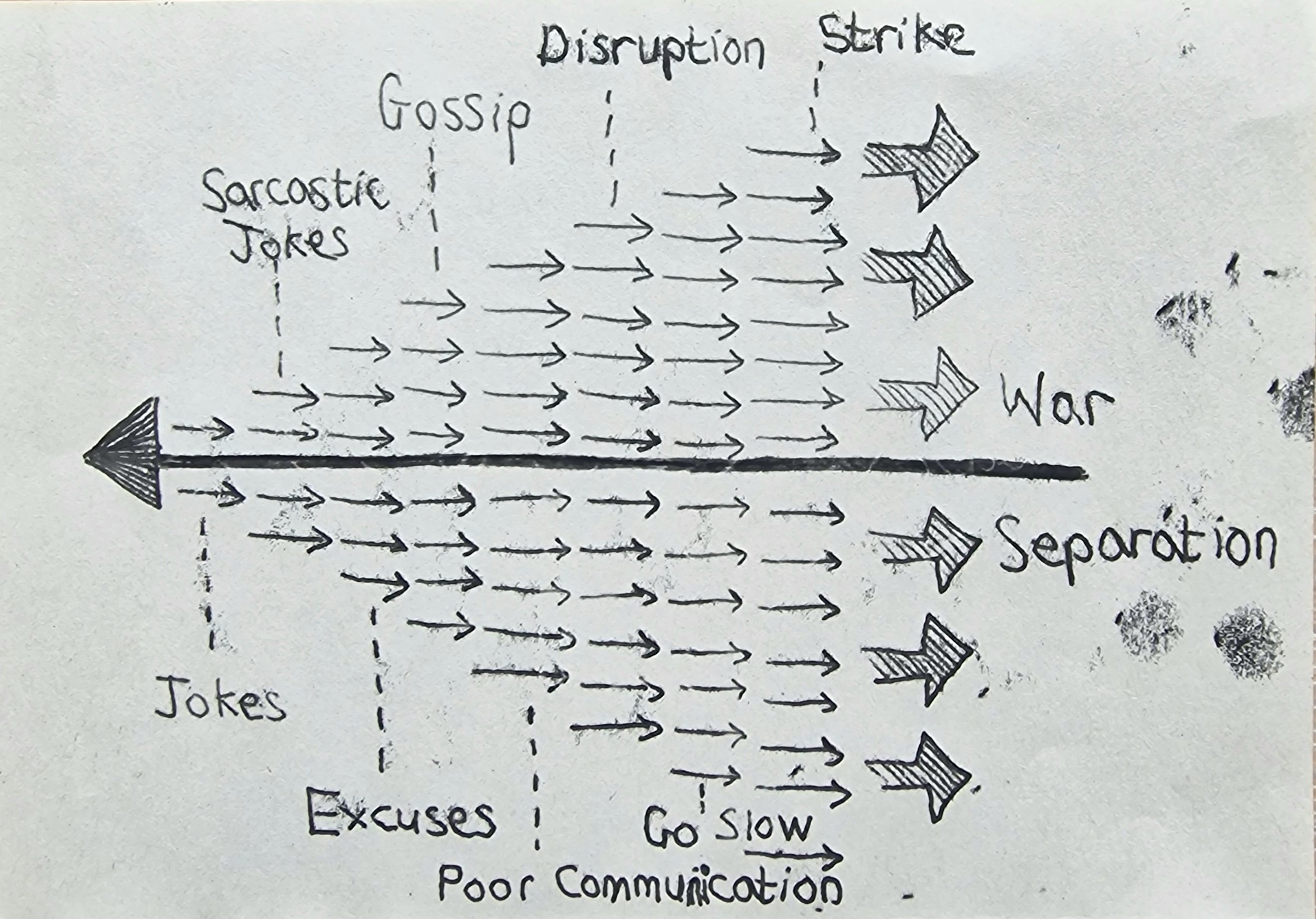

Firstly, the resistance line. Having personally experienced and lived the behaviours of the resistance line in a previous organisation, this concept immediately resonated. We have all felt, to varying degrees, a resistance to change. Any change management professional will tell you that change cannot be done to people, it needs to be done with people. If an individual, team, or group of people are going through a period of imposed or unavoidable change, here is some behaviour to look out for:

Jokes / sarcasm

Excuses

Gossip

Disruption

Communication breakdown

Strike

War / separation

Once we become aware of these behaviours we have the choice to intervene, understand and manage them, and of course integrate the wisdom that comes from understanding the resistance.

Similarly to the the resistance line, we can look out for the six communication vices outlined in Deep Democracy:

Not being present - we are all guilty of this, particularly in virtual meetings. Whilst the ability to be present can be impacted by factors such as stress, tiredness, physical environment etc, it is important to have the intention to be fully present as this demonstrates respect for others, and a willingness to be open and engage in the process at hand.

Interrupting - whilst interruption can sometimes be associated with excitement of being involved in the conversation and wanting to get your point across, it is indicative of an environment that does not provide adequate time or processes to explore the topics or issues in the depth required. It can of course have more malicious intent, when one person wants to demonstrate power by actively shutting down someone else and disregarding their contribution.

Radio broadcasting - we’ve all got that relative who blurts out a random comment or tries to start a new story in the middle of a completely different topic of conversation. This one requires someone to keep the conversation on track until it is time to move on. Staying with the flow of the conversation can help maintain connection in the group.

Indirect speaking - we can recognise this when someone is not speaking from their own personal experience and point of view; uses vague and general language; or speaks on behalf of someone else. Depending on the power dynamics in the room, this person may be too afraid to say how they really feel or think, or they may be actively creating confusion and avoiding any sense of accountability.

Sliding not deciding - similar to radio broadcasting, this is when a group changes or moves on to a new topic without resolving the current one.

Questioning - being able to ask questions is an important part of group processes, whether it is for clarification or inquiry purposes. However, there are times when people hide their views in the form of a question.

Reclaiming power from the censor - finding your voice

The question of safety was asked by a member of our group on day one of the Deep Democracy training. Agreeing on safety, acknowledging individual experience and being aware of power within the group were threads we explored throughout our time together. In the final day of the three day training we explored both perspectives of the question, “Deep Democracy is about shifting power and allowing for each voice to be heard.”

It was a rich sharing, with many nuanced perspectives. A reminder that whilst the group shares an experience, within that, individual experiences can vary greatly. Whilst facilitation processes actively centre inclusion and participation, at some point the responsibility of the facilitator ends, and the responsibility of the individual within the group, to find and use their voice, begins. Finding our voice is not an immediate process. It takes time; requires us to get out of our comfort zones; be curious about ourselves and courageous with others. All this cannot happen when we are alone. Being in a group that brings compassion, vulnerability and patience to a process of communication, is a powerful way to connect with and find our authentic voice. And Deep Democracy is one tool to support us getting there.

Finding a voice is the antidote to the Censor, as described in Starhawk’s book, Truth or Dare

A huge thank you to Payam Yuce Isik of Tribe for leading this training with grace and wisdom. In particular your masterclass in listening and reflecting the feelings and thoughts of the group. And thank you to the other participants for sharing openly and courageously throughout our three days together.